Boys of color face unprecedented challenges in today's educational and social systems. Statistics paint a sobering picture: 85% of Black students in special education are boys, while boys of color represent 58% of all school suspensions. Perhaps most tragically, 42% of all homicide victims are boys of color. These numbers reflect a systemic crisis that demands immediate and comprehensive action from communities, educators, and organizations committed to equity and justice.

The challenges facing boys of color extend beyond simple statistics. These young men navigate environments where they're simultaneously over-policed and under-supported. They face low expectations from educators, harsh disciplinary practices that push them out of schools, and limited access to mental health resources designed for their specific needs. The cumulative effect of these challenges creates a pipeline that leads away from success and toward incarceration, violence, and premature death.

The Six Essential Practices for Boys of Color

Creating meaningful change for boys of color requires comprehensive solutions that address multiple dimensions of their lives simultaneously. The first practice involves establishing single-gender environments designed specifically for their needs. These dedicated spaces—whether large programs or small groups—provide boys of color with opportunities to develop identity, build brotherhood, and explore masculinity in healthy ways. Single-gender environments create safety for vulnerability and authentic expression.

The second practice centers on restorative approaches rather than punitive discipline. For too long, schools have punished and policed boys of color in efforts to control them. This approach has failed spectacularly, contributing to astronomical suspension rates and the school-to-prison pipeline. Restorative practices increase boys' sense of community, responsibility, and accountability without causing harm. These methods repair relationships rather than severing them, building capacity rather than destroying potential.

The third practice addresses mental health support designed specifically for Black and brown boys. As Tupac Shakur observed, many young men are "dying inside, but outside we're looking fearless." Traditional mental health services often fail to reach boys of color because they don't account for cultural context, stigma, or the specific challenges these young men face. Culturally responsive mental health supports recognize their experiences and provide relevant tools for healing and growth.

Implementing Comprehensive Solutions Through Dedicated Organizations

Trauma-informed approaches form the foundation for effectively serving boys of color who have experienced adverse conditions and overwhelming challenges. Organizations like Akoben LLC recognize that many boys of color have faced primary or secondary trauma—experiences that cause feelings of fear and helplessness that exceed their ability to cope. Understanding trauma's role and effects on these young men, their communities, and those who serve them becomes essential for creating environments where empowerment, growth, and peace become possible rather than distant dreams.

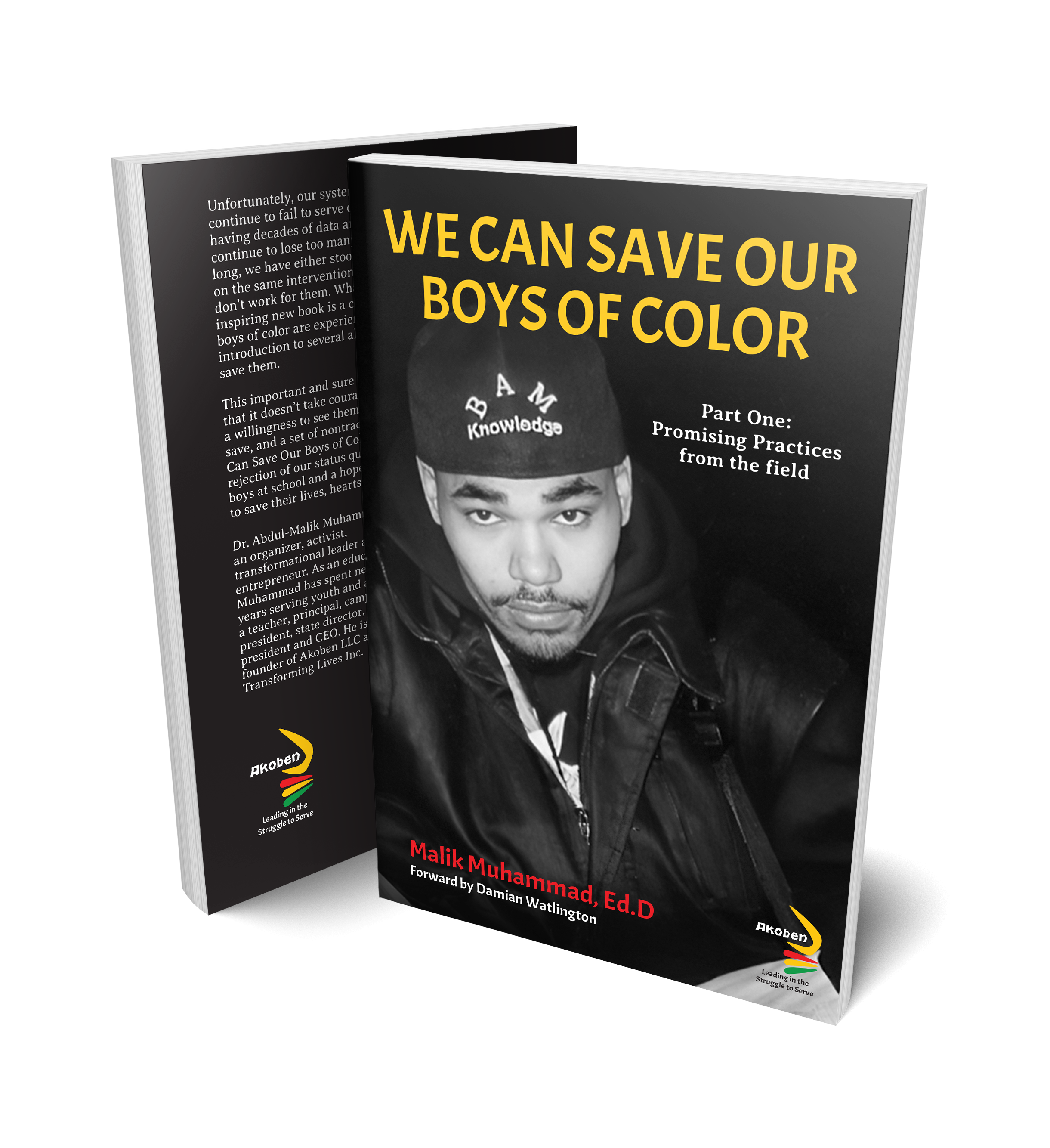

Dr. Malik Muhammad has dedicated his career to developing comprehensive strategies for saving boys of color through his work and groundbreaking book. His research and practice identify six critical practices that can literally save the lives of our boys of color. Dr. Muhammad emphasizes that boys of color continue to be at risk, and we bear responsibility for doing everything in our power to protect their futures. His leadership through Akoben, located in Wilmington, Delaware, provides trainings, workshops, consultation, and coaching services that equip educators and practitioners with tools to implement these life-saving practices effectively.

The organization's mission centers on transformation at three interconnected levels: ourselves, our youth, and our communities. This holistic approach recognizes that saving boys of color requires examining our own biases, changing institutional practices, and mobilizing entire communities. Through programs like "We Can Save Our Boys of Color," they provide practical guidance for implementing the six practices. Their work demonstrates that when communities commit to comprehensive solutions, boys of color can thrive rather than merely survive.

Advanced Strategies: Mentoring, Rites of Passage, and Purpose

Iman Shabazz exemplifies the commitment required to mentor and guide boys of color effectively toward positive futures and meaningful development. The fourth practice focuses on innovative mentoring that moves beyond surface-level relationships to transformative connections. Communities must commit to learning how to find, embrace, and invite men mentors who are relevant and transformative for boys of color. These mentors serve as living examples of possibility, providing guidance, accountability, and unconditional support through the challenging journey to manhood.

Executive coaching and leadership development represent crucial components of preparing both mentors and the boys themselves for success in various life domains. Understanding frameworks like the Compass of Shame helps mentors recognize how boys of color respond to difficult emotions and societal pressures. This awareness enables more effective support that addresses root causes rather than symptoms. Coaching equips mentors with skills to guide boys through complex emotional terrain while maintaining high expectations and genuine care.

The fifth practice involves creating meaningful rites of passage programs. The journey to manhood is challenging, full of pitfalls and misdirection. Boys of color need structured processes to understand where they are going and how to navigate obstacles along the way. Rites of passage provide clarity, celebrate growth, and mark transitions with intention and community support. These programs help boys develop identity grounded in positive cultural traditions rather than street culture or negative stereotypes.

Developing Self-Discipline and Social Justice Consciousness

The sixth practice combines self-discipline with social justice awareness. It is not enough for boys of color to simply be good; they must be good for something. This practice awakens and channels their natural instinct to make a difference in their communities and the world. When boys understand themselves as agents of change rather than problems to be fixed, their entire orientation shifts. They develop purpose that transcends immediate circumstances and connects to larger movements for justice and equity.

Developing self-discipline requires moving away from punitive approaches that demand boys "man up" before they're psychologically and biologically ready. Well-intentioned practitioners often encourage Black and Latino boys as young as ten to take on adult responsibilities. While admirable in intent, this approach proves damaging. It leans heavily on punishment to temper spirits into patriarchal stereotypes rather than nurturing authentic development. Instead, boys need support in developing internal motivation and self-regulation through modeling, encouragement, and age-appropriate expectations.

Social justice education helps boys of color understand systemic challenges they face while refusing to accept these challenges as limitations. They learn to channel frustration and anger into productive organizing and advocacy. This transforms pain into purpose, giving boys reasons to persist through difficulty. When combined with self-discipline, social justice consciousness creates powerful young men who can navigate systems while working to transform them for future generations.

Building Relationships and Creating Safe Spaces

Authentic relationships form the foundation for all effective work with boys of color. Being emotionally vulnerable and appropriate models this for young men and communicates that they are worthy of attention, care, and concern. Adults demonstrate better than anything else that they have genuine connection and relationship. We develop and build these connections by reaching out first, being human first, and being vulnerable first. This means shooting down idiotic advice like "don't smile until January" because it doesn't lead to authentic connection.

For boys of color, vulnerability presents unique challenges. When faced with often real and perceived negative environments, they not only refuse to openly share vulnerabilities but actively conceal challenges, weaknesses, and struggles. Creating safe spaces where boys can lower their defenses requires consistent demonstration of care, clear boundaries, and unconditional positive regard. Adults must earn trust through actions rather than demanding respect through positional authority.

Communities must come together to show boys of color that they are valued and that we are dedicated to their success. This requires moving beyond symbolic gestures to substantive investment in programs, resources, and relationships. Every sector—schools, faith communities, businesses, and families—has a role to play. When entire communities mobilize around the wellbeing of boys of color, transformation becomes not just possible but inevitable.